NVAP Reference Guide: Equine Identification

Control and Eradication

- Brucellosis

- Johne’s Disease

- Pseudorabies (PRV)

- Tuberculosis

- Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies

- Scrapie

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)

Poultry

- National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP)

- Avian Influenza (AI)

- Exotic Newcastle disease (END)

- Equine Disease

Animal Health Emergency Management

- Animal Health Emergency Management

- Emergency Response Structure

- National Response Framework (NRF)

- National Incident Management System (NIMS)

- National Animal Health Emergency Management System (NAHEMS)

- Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)

- FAD Recognition and Initial Response

- National Animal Health Emergency Response Corps (NAHERC)

- Notifiable Diseases and Conditions

- WOAH and International Standards

- Cleaning and Disinfection

- Disease Surveillance

- Laboratory Submissions

Animal Movement

- Interstate Regulations

- Interstate Movement of Cattle, Horses, Swine, Sheep and Goats

- Issuing Interstate Animal Movement Documents

- International Animal Movement

- Issuing International Health Certificates (IHCs) for Live Animal Movement

- Common Problems Observed on Certificates for Live Animal Movement

Animal Identification

- Animal Identification

- Cattle Identification

- Swine Identification

- Equine Identification

- Sheep and Goat Identification

- Fowl Identification

- Compliance and Regulations

Appendix

With the current high level of interest within the horse industry regarding equine census estimates and potential disease movement, new methods for equine identification are rapidly being researched and developed. Many breed registries are either contemplating change or are in the process of changing the methods by which they identify horses. For that reason, APHIS does not list specific breed requirements for identification. Instead, this manual describes equine identification technologies currently in production or the late stages of development in the United States.

You should consider multiple technologies when establishing or determining the unique identification of a horse. When shipping a horse interstate, APHIS recommends that the accredited veterinarian contact the state animal health officials of the state of destination to verify the specific identification requirements of the receiving state.

When shipping a horse internationally, the accredited veterinarian should contact the APHIS –VS Area Offices to determine the identification requirements of the receiving country.

Types of identification and background, technology, and usage Hot Iron or Fire Brand

Background: Introduced by Spanish settlers (early 1800s).

Technology: Heated brand (by fire or electricity) applied to dermis at variable sites.

Usage: Individualized ranch or farm brands.

Lip Tattoo

Background: Introduced by U.S. Army (late 1800s).

Technology: Ink and perforating plates applied to upper lip (buccal) mucosa.

Usage: Racing thoroughbreds (all thoroughbreds registered by genetic typing).

Freeze Mark or Cold Brand

Background: New popularity for humanitarian reasons (recent decades).

Technology: Cryogenically cooled brand applied to dermis of the neck.

Usage: All Standardbreds (right neck) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wild horses/burros (left neck); Arabians have discontinued; many nonregistered “backyard” and farm horses to deter theft.

Electronic Identification (RFID)

Background: Currently the most popular and computer-compatible (this decade).

Technology: Implantable transponders are activated when interrogated by radio frequency readers; thus, such units are known as Radio Frequency Implantable Devices (RFIDs). RFID readers are used to identify and display transponders' alphanumeric characters. Microchips are implanted in the left nuchal ligament (the USDA- and FDA-approved anatomical implant site for all equids in the United States). The International Standards Organization (ISO) now brings all major electronic identification and RFID manufacturers to unified standards. Universal readers are available.

Usage: Many foreign breed registries in North America, all horses tested for EIA in the State of Louisiana, and many nonregistered equids.

Integrated Circuitry (IC) Cards (“Smart Cards”)

Background: This future technology is currently incorporated in several pilot studies.

Technology: An electronic tool that links any desired information to the equid’s unique identification and stores these data on an IC chip built into a device resembling a credit card. The card, retained by the owner or other custodian, can be accessed only by persons using a second authorization card. These cards may be used in local management of the horse or herd by the owner, custodian, trainer, veterinarian, or other authorized person or may be connected via the Internet to regulatory agencies, breed associations, show offices, or other professional affiliates.

Usage: None currently in equids.

Iris Biometrics

Background: This future technology is based on a 1994 patented technique in people.

Technology: Iris “code” by “demodulation” of iris pattern (geometric structure) is done through complex mathematics. The benefits of equine applications are that using the portable digital camera for imaging is fast and noninvasive.

Usage: None currently in equids.

Retinal Biometrics

Background: New bovine–porcine technology attempts application to the equine retina.

Technology: The vascular pattern of the retina is recorded uniquely by algorithm. Benefits in equine applications are that the use of the portable digital camera for imaging is fast and noninvasive; additionally, it is designed to include a global positioning satellite (GPS) receiver to allow automatic encryption of date, time, and location of image capture.

Usage: None currently in equids.

Equine Colors and Markings

Determination of equine coat colors can be a challenge even to experienced equine identifiers. The names of most colors used to describe equids are unique to the species and can be counterintuitive; even experts often disagree. Some breed registries recognize only a limited number of colors; others are, by definition, limited to a single group of colors (e.g., Cleveland Bay). The best approach for equine identification is to use the basic terminology common among most breeds of horses, mules, or donkeys with a notation if the technical name of the color does not match the actual color observed. For example, it may be appropriate to describe an older grey horse as “grey (appears almost white)” where possible.

APHIS will not attempt a summary at this level of detail here. Registry rules (which can be different between breeds), historical and cultural influences, and even regional differences within the United States all contribute to the difficulty in describing a single color-naming system. This section on equine identification aims to explain the prevailing basic terminology useful for identifying equids for animal health or regulatory purposes.

For identification, mules are usually described using the same terms as horses or using the ordinary names of colors. The traditional terms for describing the color of donkeys (including burros and all asses) will be briefly described here. However, they are also often described using the ordinary names of colors. There are a few good references on equine colors, and the reader is encouraged to review those works for a more detailed discussion of the subject.

Colors

The base color of horses occurs independently of any white superimposed on the underlying coat color. In addition to the white markings that may appear on the head or legs, white may appear on the body. When describing a horse’s color, it is important to recognize the “points” of a horse as black or not black, whether or not white markings are present. The points are the mane, tail, lower legs, and ear rims and are as important to recognize as the base color to name a color properly. Foals are often born a different color than they will be as adults. The adult color often appears around the eyes and on the face first. Usually, foals shed out to their adult color around 2 months of age.

Horses have three primary base coat colors: bay, chestnut, and black. These colors are modified by various factors (genes), including dilution factors, to produce a huge variety of shades and specific color patterns. Brown (which some consider synonymous with dark bay) and sorrel (usually considered synonymous with, or a variation of, chestnut) are also basic colors that can help identify most horses. Common modifications of the base colors include the colors grey/gray and roan, and the pinto and Appaloosa color patterns. Finally, there are a host of colors created by modification or dilution factors that are given distinct names. Those considered here include buckskin, dun, palomino, cremello, and white. APHIS –VS gratefully acknowledges the cooperation of The Jockey Club in allowing us to reproduce common head and leg marking figures.

Basic Horse Colors

- Bay: The coat color varies from yellow-tan to dark blood-red to brown and almost black. The points (mane, tail, lower legs, ear rims) are always black unless white markings are present. Some registries use dark bay/brown as one color.

- Dark bay: The coat is brown with areas of tan on the head, shoulders, flanks, inside of the thighs, and the upper portions of the legs. The points are always black unless white markings are present. This color is also sometimes called brown.

- Chestnut: This color includes any shade of red from very light (blonde, sorrel) to dark red (liver chestnut). A chestnut can be so light in color as to give the appearance of a palomino or so dark that it looks brown or shows numerous black hairs throughout its coat. A chestnut always has points the same color or lighter compared with the body; the points are never black. In some breeds and much of the Western United States, sorrel is used synonymously with chestnut.

- Sorrel: A red to reddish yellow base coat with lighter shades of similar color (may be flaxen or blonde) in the mane and tail. This color is sometimes used synonymously with chestnut.

- Black: The entire coat is black excluding any white markings that might be present. The mane, tail, muzzle, flanks, and legs must be all black with no areas of brown or tan coloration.

- Brown: Usually synonymous with dark bay and sometimes appearing almost black but with lighter tan coloration on the muzzle, flanks, or both. The points are always black unless white markings are present.

Modifications of Basic Coat Colors

- Grey/Gray: Grey is a color modification superimposed over any base color on the body, head, and legs. The coat is a mixture of dark (usually black) and white hairs that become predominantly white with age. The grey horse always has dark/black skin.

- Markings on light grey horses can best be seen by noting the underlying pink skin in the area of the marking. In the young horse, black hair predominates, but as the horse ages, the white hair increases, and the markings tend to fade. A grey horse may have distinct white or faded markings and always a grey or black mane, tail, and legs.

- Flea-bitten Grey: Flecks of the base coat (usually red but may be black) show through mostly white body color.

- Roan: Most of the coat is a mixture of colored (usually red) and white hairs, with the head and legs darker than the body. Colored hair predominates. As the horse ages, the proportion of white hair may increase, but usually not to the extent this occurs in grey horses. If the red hair comes from the chestnut pattern, the mane, tail, and legs will be red. The mane, tail, and legs will be black if the red hair comes from the bay pattern. Roan horses may have distinct or indistinct white markings.

- Strawberry roan: The coat color is a mixture of red and white hairs. The base color is chestnut/sorrel, and the points are not black.

- Blue roan: Similar to roan, except there is a mixture of black and white hairs; the base color is black.

- Red roan: Also called bay roan. The coat color is a mixture of red and white hairs, but the base color is bay, and the points are black.

Patterns Superimposed on Base Colors

- Appaloosa: No single color is associated with Appaloosas. The term describes the appearance of an indefinite number of different white or dark spot patterns on a base color or solid white area. The spotted areas classically appear on the hip but may also occur on the loin, back, or over the entire body. The colors are named the base color followed by “Appaloosa” (e.g., bay Appaloosa, blue roan Appaloosa, etc.). As a breed, the color is also associated with mottled or particolored skin typically found around the eyes and on the nose, lips, vulva or sheath, white sclera, and vertically striped hooves. Any combination of white markings is possible.

- Leopard Appaloosa: Has the appearance of a white horse covered with dark spots that are usually reddish.

- Pinto: Any of several breeds of horses with large, irregular, asymmetric areas of white (with underlying pink skin) and a base color on any body area. Any base color is possible. This color is either named by the base color (e.g., chestnut pinto) or by describing the colors seen using common terms (e.g., red and white pinto). Although a specific breed and color registry, the term “paint” is often used interchangeably with “pinto” (e.g., black and white paint).

- Overo: Pinto pattern characterized by white that usually does not cross the back. At least one leg and often all four are dark colored, the body is often predominantly the base color, and the tail is usually one color.

- Tobiano: Pinto pattern with white across the back. Flanks are usually dark colored; generally, all four legs are white, and the tail is often two colors.

- Tricolor: Nontechnical term for a pinto with black (usually in the mane or tail) and white areas on top of a base color.

Dilution Modifications of Base Colors

- Buckskin: A cremello dilution modification of any base color. Typically, it is a gold or yellowish body color with a black mane and tail. Buckskins are usually black on their lower legs. Usually, buckskin describes horses without a dorsal stripe.

- Dun: A general term for any of several light or dilution colors with a dark dorsal stripe (lineback dun). Body color can be yellowish or gold, like a buckskin, or red, like a chestnut. Mane and tail may be black, brown, red, yellow, white, or mixed. Other primitive markings may be present, such as zebra stripes on the legs or a transverse stripe across the withers.

- Red dun: A chestnut/sorrel dun with a yellowish red body; mane, tail, and dorsal stripe are darker red.

- Palomino: Body color is usually a golden yellow; mane and tail are blonde or almost white. Palominos do not have dorsal stripes.

- Grullo: Usually characterized by slate- (blue-grey) or mouse-colored hair (not a mixture of black and white hairs, but each hair is mouse-colored) on the body with a black mane and tail. Body color may be darker shades of beige. Grullos are usually black on their lower legs.

- Cremello: The palest horses that are not white. Usually, very light beige or cream colored. Cremellos have pink skin and blue eyes.

- White: A rare coat color of pure white with pink skin and dark-colored eyes. White horses are not true albinos; albinos have pink eyes. Horses that appear to be white but have dark skin are actually grey.

Donkey Colors

Some donkey colors are the same as those of horses; others are unique to the donkey. The points of a donkey are different from those of a horse. When describing the color of donkeys, “points” refer to the muzzle, eye rings, belly, and inside of the upper leg, which are almost always cream-colored. Cream-colored points may be called “white points” or “light points.” The color of a donkey’s points does not affect the name of the body color, but points are usually described separately as light instead of dark, blue, or black points. The areas described as points in horses (mane, tail, ear rims) are called trim when describing donkey colors but have the same significance when naming colors.

- Grey (Dun): This is the donkey's most common coat color. It is an ash-grey or bluish-slate color with a dark dorsal stripe. This color is not a true grey as in horses because it does not become lighter with age. Cream-colored points are typical.

- Blue Burro: Another name for the grey dun.

- Black, Brown, Dark Brown, Black-Brown: Each refers to that body color with light points unless otherwise noted.

- Red, Chestnut, Sorrel: Refers to a chestnut, sorrel, or reddish body color.

- Pink: Very light strawberry red color. They may have pink skin.

- Spotted: White spots on the body of any base color; it can also appear like dark spots on white.

- Roan: White hairs mixed with colored hairs on the body and head.

Markings

Natural markings include patterns of white on the head and legs, hair whorls (cowlicks), scars, and blemishes. Many white markings on the head and legs have common terms in the horse world. As determined by the purpose, white markings may be simply named, drawn in a picture, described in detail, or photographed. White markings always have underlying pink skin, which is sometimes used to describe the exact margin of the marking (e.g., “ snip extending into left nostril”). Most markings are solid white but can be mixed with the base coat color. Leg markings are always named by the most proximal extent of the marking on a given limb (Fig 5). Leg markings may be described by naming the anatomic location of the most proximal extent of the marking (e.g., cannon) or using traditional terms (e.g., sock). The anatomic terms are preferred for identification because not all breed registries agree on the lay terms.

Markings produced after birth are considered acquired markings. Tattoos, brands, freeze marks, scars, and pin-firing marks are the most common examples. The location and shape of these marks are sometimes also described as markings. On plain-colored horses without natural white markings, these features can be very useful, along with hair whorls to identify a horse. Other variations seen on the coat are not generally considered markings. Dapples are a repeating pattern of slightly darker and lighter hair in small circles. Dappling is most common on grey horses but may occur with any color. Dappling is not permanent but may vary in any particular individual with season, nutritional status, or physical condition. For this reason, dapples are not generally recorded for identification. Ticking is small spots of flocks of white hair, often only consisting of several adjacent white hairs that can occur in the base coat. Ticking tends to increase with age. Ticking can generally be noted when identifying a horse; the exact location and amount of ticking may change over time.

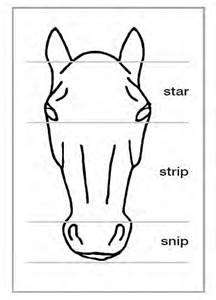

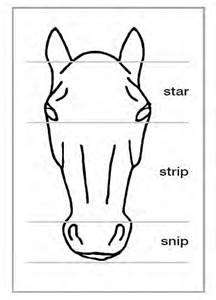

Common White Head Markings (Fig. 4)

- Star: A white spot or any shape found on the forehead above the rostral corner of the eye. The location, size, and shape can be described or drawn in relation to other face structures where appropriate.

- Bordered star: Having the coat color mixed with the white hair along the outer edge.

- Strip: A white marking on top of the nasal bones starting at the eye level or below and ending on or above the proximal edge of the nostrils. It may be connected or disconnected to a star. The width, length, and type (connected, disconnected, broken) can be drawn or described as needed. Also, it may sometimes erroneously be called a stripe.

- Bordered strip: The coat color is mixed with the white hair along the outer edge.

- Broken strip: The strip is disconnected from itself at one or more points.

- Snip: A separate white or flesh-colored marking usually found between the nostrils. It may extend into the nostril or to the upper or lower lip, according to some breed registries.

- Upper/Lower lip, chin: White or flesh-colored markings in these areas are named separately by some registries. It is also sometimes called a chin spot or patch.

Star/Strip/Snip/Upper/Lower Lip Connected: Any adjacent combinations of these markings may be described as connected when they touch. For example, “star and strip connected, lower lip disconnected” or “star, strip, and snip connected.” - Stripe: Usually used to describe a long, narrow star, strip, and snip connected.

- Blaze: A wide, connected star, strip, and usually snip extending laterally below the top of the nasal bones but not including the eyes or nostrils.

Bald: A very wide blaze including at least one eye and usually both nostrils. - Chestnuts (on the legs)/Night eyes: Chestnuts are hard, horny growths or patches of cornified skin found inside the horse’s legs. Chestnuts may grow long, but when flat have a distinct shape. The presence, location, and shape of the chestnuts can help uniquely identify a horse.

White Leg Markings (fig. 5)—

- Partial heel: The medial (inside) or lateral (outside) heel may be white; called a partial heel on the white side.

- Heel: Both heels (the entire heel) of the hoof may be white.

- Coronet/Coronary band: White begins at the hoof and extends proximally about an inch or less than halfway up the pastern.

- Half-pastern: The leg is white from the hoof up to and including the lower half of the pastern.

- Pastern: The leg is white to the top of the pastern below the fetlock.

- Fetlock/Ankle: White extends up to the top of the fetlock.

- Half-Cannon/Half-Stocking/Sock: White extends from the hoof up to and including the lower half of the cannon bone.

- Cannon/Three-quarter Stocking: White extends to the proximal end of the cannon bone below the carpus (knee).

- Knee/Hock/Stocking: White extends up to or just to the top of the carpus (knee) or tarsus (hock).

- Above Knee/Hock, High White: White extends above the carpus (knee) or tarsus (hock).

- Ermine spots: Refer to small, dark spots in white leg markings that are usually found just above the hoof.

Other Natural Markings

- Hair Whorl/Rosette/Cowlick: Hair whorls are patterns, usually circular, in which the direction of hair growth changes. Hair whorls are permanent and cannot be brushed away or clipped out. There is usually one whorl in the center of the forehead, often between the eyes. These single whorls are not typically described as unique markings; however, the distance above or below the eye level could be noted. Less frequently, two or more whorls are found on the forehead. When present, the number and locations of multiple whorls should be described if appropriate. The presence (and location if present) or absence of any whorls or cowlicks on the side of the neck near the mane can also be a useful aid in identification, particularly when a horse has few white markings and no tattoo, brand, or similar feature.

- Dimples/Prophet’s thumbprints: Permanent, easily seen indentations in muscles just under the skin. Dimples are usually found at the point of one or both shoulders and in the neck muscles.

- Curly coat: A rare variation of hair growth resulting in exceedingly curly body, mane, and tail hair. The curly trait is inherited and is not related to hirsutism. The curly appearance occurs to varying degrees but usually affects the mane and tail (as opposed to hirsutism), and curly horses may shed out their mane and tail in addition to their body coat in the spring.

- Chestnuts (on the legs)/Night eyes: Chestnuts are hard, horny growths or patches of cornified skin found inside the horse’s legs. Chestnuts may grow long but when fl at have a distinct shape. The presence, location, and shape of the chestnuts can help uniquely identify a horse.

Acquired Equine Markings

- Tattoos: The tattoo is a group of numbers with or without a letter applied to the underside of the upper lip. In Thoroughbred horses, the letter indicates the birth year of the horse (A=1997, B=1998, etc.), and the numbers correspond to the numbers found on the registration certificate. Imported Thoroughbreds have an asterisk rather than a letter in their tattoo.

- Scars: Many scars produced by accident are permanent and can be seen throughout a horse's life; they should, therefore, be noted.

- Pin firing marks: Although not common today, the procedure of pin firing the legs of a horse leaves permanent scars. This information can be useful for identification.

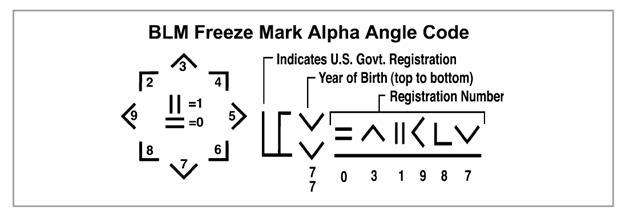

- Brands: A hot or cold (freeze mark) brand may be found in various areas but is most commonly found on the hip or neck. Some brands are for breed or farm identification; others use numbers or symbols unique to each horse. For example, the Bureau of Land Management uses an angle-numeric system for recording unique numbers on the left side of the neck under the mane (Fig. 6).

Information on aging a horse by teeth using color photos is contained in Appendix G at the end of this Reference Guide.